Thanks to the Society of Financial Service Professionals (FSP) both for its leadership in addressing emerging and evolving issues around the application of Prudent Investor principles to the asset that is life insurance and for its cooperation and permission to make this special program available to Veralytic subscribers and followers for a 25% discount. This FSP panel of experts brings a level of knowledge along with their reputations for having a robust conversation of the duties assumed by trustees of Trust Owned Life Insurance that you should not miss. Don’t miss the special offer towards the end of this article…

Program Overview

The Uniform Prudent Investor Act (UPIA) imposes a duty on all trustees/fiduciaries to manage, monitor, and evaluate assets and investments under their care for the benefit of the beneficiaries of the trust, a duty which also applies to Trust-Owned Life Insurance (TOLI). Despite numerous professional articles pointing out the applicability of UPIA to TOLI, the vast majority of trustees/fiduciaries have not applied these statutes uniformly with respect to TOLI. The panel of experts in this program examines the risk management of life insurance, identifying the techniques and resources available to trustees to evaluate permanent life insurance policies, and reviews UPIA and its applicability to TOLI. As follows:

Gary L. Flotron, MBA, CLU®, ChFC®, AEP® - past president of the National Association of Estate Planners & Councils (NAEPC) and moderator of the panel discussion - begins explaining the purpose of the program is to explore the compliance, risk management and evaluation of permanent life insurance by setting the stage with some imagery.

“Imagine 2 rooms that both contain a rather large elephant that is pretty much being ignored in both rooms. In the first room are Trustees and fiduciaries that hold permanent life insurance in their care. The elephant in their room is the UPIA and its applicability to TOLI. In the second room are life insurance professionals who advise the trustees, fiduciaries and other clients on the evaluation, selection and management of permanent life insurance policies. Their elephant is a 1992 Society of Actuaries Task Force Report on Policy Illustrations. This report clearly states that policy illustrations cannot be used to predict future values of a policy, nor can they be used to compare one policy to another, even if they are the same type of policy.”

“Now imagine both of these rooms with elephants are converging. The catalyst to this convergence is the landmark case Cochran versus Keybank.”

Larry Brody, JD, LLM, AEP® (Distinguished) – partner in international law firm Bryan Cave and among the most sought‑after author and speaker on the use of life insurance in estate and employee benefit planning – provides the legal perspective by reviewing the applicability of UPIA and relevant case law to TOLI and cites Veralytic work-product (i.e., 2 articles about the Cochran v. Keybank case co-authored by Veralytic founder and inventor – Barry D. Flagg, CFP®, CLU, ChFC – published in Steve Leimberg's Estate Planning Email Newsletter), along with another article from Steve Leimberg's Estate Planning Email Newsletter discussing the French v. Wachovia case (about which Flagg was interviewed on JHAM Radio – click here to listen to the broadcast), and the ACTEC series of 4 articles on the management of life insurance policies and life insurance trusts.

Brody begins by citing a number of very interesting statistics from a survey of personal (i.e., non-corporate fiduciaries) trustees about their activities (or lack thereof) and delves into the 5 most important/relevant sections of UPIA to TOLI (in numerical order), as follows:

1. UPIA SECTION ONE: PRUDENT INVESTOR RULE.

Brody discusses the definition of prudence as defined by UPIA, the origins and legislative history of UPIA, that UPIA is the default rule, and has been now been adopted by all States but varies by State and includes a useful list of States which have enacted laws that effectively reduce or eliminate the local Prudent Investor Rule as it applies to TOLI. Brody also explores the unique relationship between an ILIT trustees and the trust Grantor, and the wisdom of restricting or eliminating the applicability of UPIA to an insurance trust given its impact on the beneficiaries.

2. UPIA SECTION TWO: STANDARD OF CARE.

Brody discusses and references the duties UPIA requires, namely: the Duty to Monitor, the Duty to Investigate (i.e., to examine information likely to bear importantly on the value or the security of an investment), and the Duty to Manage, and include the “laundry list of the circumstances that the trustee is required to take into account in investing and managing the assets of the trust.” Brody makes special note that “one of the important aspects of this provision of the Act is the ‘Duty to Monitor’, and the Comments to the Act provide that all of these provisions apply to both investing and managing trust assets. It defines the word managing as embracing monitoring; that is the trustee’s continuing responsibility for ‘oversight of the suitability of investments already made as well as the trustee’s decision about making new investments.’”

3. UPIA SECTION THREE: DIVERSIFICATION.

Brody observes that “diversification is a critical issue for all trustees, but in some ways especially for trustees of trusts that own life insurance policies” and explains that the Comments to the Act recognize that “circumstances can overcome [this requirement to diversify].” Brody and later Schwartz both give some interesting examples of circumstances that can overcome this requirement to diversify. Brody also differentiates between diversification between life insurance and other types of assets versus diversification among different life insurers and/or different types of life insurance, and includes a useful list of cases providing guidance for where courts have upheld a trust document’s waiver of the duty to diversify and where they have not.

4. UPIA SECTION SEVEN: INVESTMENT COSTS.

Schwartz interjects “the trustee has an obligation under Section 7 to monitor and investigate the expenses within the policy. You can’t just look at the premium and the assumed rate of return. You also have to look at the underlying expenses. For example, there are companies that charge very high expenses and there are other companies that charge very low expenses. There are also agents who [discount commissions based on a larger] size of the policy whereas other agents says that is not part of my practice.” Whitelaw adds that measuring “how expenses compare to a benchmark” is one of the 5 key data points needed for a policy evaluation to both be considered facts-based and dispute-defensible, and provide the trustee with the information needed to make an informed determination. Brody also advises when considering an exchange of an inforce policy to a new policy that appears to offer lower costs that a good way to avoid potential disputes is to a) investigate and quantify the costs of both the existing inforce and new proposed policies, b) independently confirm proposed cost savings with independent research/expert opinion from a third-party with no economic stake in the outcome (which Weber added “is critical”), c) communicate this information to trust beneficiaries, and ideally d) seek beneficiary consent for the exchange in advance.

5. UPIA SECTION NINE: DELEGATION OF INVESTMENT AND MANAGEMENT FUNCTIONS.

Lastly, Brody observes “this delegation provision is a relatively new provision for trustees” and discusses the circumstances and continuing duties where a trustee may delegate investment and management functions. Brody also explores the idea of an “unskilled trustee – a trustee unskilled in the management of life insurance policies – considering delegating that function to someone who has that skill.”

Randy Whitelaw – Managing Director of Trust Asset Consultants, co-creator of The TOLI Center with one of the largest third-party administrators of TOLI, and the fiduciary expert for the plaintiff in the Cochran v. Keybank case – offers the perspective from the trust officers’ point of view and discusses how trustee fiduciaries should manage TOLI, what are the best practices to follow, and what red flag and predatory practices[1] are to be avoided. Whitelaw follows the title theme discussing …

... why UPIA/TOLI has been the impossible dream because trustees have too often been told what they “should do” but not provided “how to” guidance, and mistakenly believe they are not exposed to performance risk. Whitelaw explains TOLI is a “buy and manage” financial asset but life insurance producers provide only the “buy function” but not the “manage” function.

... when the dream can become a nightmare in situations where ILIT trustees lack life insurance expertise and fail to delegate, and/or when the risk of doing nothing is greater than the risk of doing something, and/or when corrective actions are taken based on aggressively-marketed abusive replacement schemes instead of dispute-defensible best-practices.

... how it can be a match made in heaven when unskilled trustees look to skilled trustees to follow their lead in the management of trust assets by using the same time-tested management disciplines as are applied to other trust-held assets, by identifying best-practices versus predatory-practices, by delegating monitoring and investigation functions to third-party administrators and consultants, and by using an RFP and IPS like is common for other types of trust-held assets.

Whitelaw also discusses the “red flags” that identify the potential nightmares (i.e., subjective-based, overly-simplistic policy evaluations based on predatory sales/marketing practices using illustrations of hypothetical policy values), the keys to avoiding the nightmare (i.e., fact-based, dispute-defensible policy evaluations based on established actuarial and investment evaluation methods and using objective data), and best-practices for restructuring policy holdings considering both primary-market and secondary-market options. Whitelaw concludes that corrective action is needed, that best-practices solution providers are readily available, and that trustees should seek out support services that are dispute-defensible, time-tested and litigation-tested.

Dick Schwartz, FSA, MAAA, CLU® – President of Life Insurance Analysts, Inc., co-author of the original American Bar Association primer publication Life Insurance Due Care: Carriers, Products and Illustrations, and consulting actuary responsible for the development of Veralytic benchmarks – provides the accounting and actuarial perspective, and discusses 4 key points to remember when managing trust-owned life insurance policies, as follows:

- A life insurance policy is clearly a financial asset that needs to be managed and reviewed every 1 – 2 years.

- Different policies have different types of risk, and the trustee should be aware of the risks the policy inherently presents, and think about ways to mitigate those risks.

- The client, grantor, trustee, etc. should not consider the illustration a guarantee – rather the only thing guaranteed about the illustration is that it is guaranteed not to perform as shown – and be aware that some illustrations can be used to hide the facts.

- Despite the conception advanced by a lot of insurance companies that policy exchanges are not beneficial, the truth is that policy exchanges can be beneficial if done correctly.

Schwartz then expands on the various factors to consider when determining when a policy exchange can be beneficial, namely:

- Pricing Factors (i.e., cost of insurance/mortality charges, persistency/lapse rates, policy issue and administration expenses, discounted versus non-discounted commissions, investment returns that are reasonable to expect, and insurer profit margin), and

- Risks Inherent in Each Policy Type (i.e., insurer insolvency that can be significant, volatility in and differences between hypothetical versus actual investment returns, cash value availability or lack thereof, and differences between expected versus actual policy expenses).

Schwartz concludes by reiterating that comparing illustrations is not appropriate, even though illustrations have often been used in the past to compare different policies because nothing else was available, and explains …

... the different ways trustees can mitigate risks (i.e., diversify carriers and policy type, conservative investment assumptions/expectations, don’t expect actual results to improve significantly if at all, consider policy exchange/replacement after 5 - 15 years, and consider cash value volatility in determining funding adequacy, and

...various TOLI management considerations (i.e., responsibilities of a successor trustee, frequency of TOLI reviews, changes in the insured’s circumstances, changes in planning objectives, changes in insurer’s circumstances, differences between hypothetical versus actual performance, and the break-even between new acquisition expenses versus future cost-of -insurance savings).

Dick Weber, MBA, CLU®, AEP (Distinguished) – President of the Society of Financial Services Professionals, life insurance expert for the plaintiff in the Cochran v. Keybank case, and consultant to life insurers and their agents on the topic of effective and ethical selling – provides the life insurance fiduciary perspective and discusses applying to life insurance the same financial and investment management and evaluation techniques that have been used for years in the trust arena, like benchmarks, measuring standards, Monte Carlo simulations, and probability analysis.

Weber’s comments focus on the differences between the reality of actual policy performance versus the illustration of hypothetical policy values (which he characterizes as “Two Alternate Universes”), and the dangers of over-reliance on illustration of hypothetical policy values. Instead, Weber encourages a deeper understanding of …

... the impact of life expectancy on the funding requirements/adequacy in a given life insurance policy.

... the differences between guaranteed policy styles (i.e., where premiums and/or death benefits are guaranteed) versus non-guaranteed policy styles (i.e., where premiums represent a calculated and changing funding amount that is needed to cover policy expenses, which can and do change, given a policy crediting rate, that varies both over time and by product type).

... the lack of transparency for policy expenses and how not knowing the consequence of what is being charged for cost of insurance (COI), sales charges, policy fees, premium loads, etc. makes it more difficult to compare the underlying pricing of one policy to another.

... the reasonableness of premium calculations and performance expectations for both newly issued policies (e.g., universal life products where performance expectations proved overly-optimistic and premium calculations were thus inadequate) versus premium calculations and performance expectations for inforce policies (i.e., it is unlikely that older blocks of policies are going to see an upward swing in their crediting rates even when interest rates go back up in the economy).

... the dangers of calculating premium funding requirements from current-assumption illustrations of hypothetical policy values (i.e., the insurer’s current and best view of the future) versus calculating more reasonable premium funding expectations using actuarially derived (i.e., based on the law of large numbers) stochastic (i.e., Monte Carlo) methods.

... the differences between illustrations that appear to offer the “best price” at a moment in time (e.g., the premium calculated from a current assumption illustration of hypothetical policy values) versus seeking out those products offering the “best value” (e.g. measuring against actuarially derived expense benchmarks, utilizing statistically credible models to model volatility, and calculating premium funding requirements to reasonably cover such costs over a reasonable life expectancy).

... the 4 remediation possibilities for under-funded policies, namely: 1) increase premium funding, 2) decrease death benefits, 3) exchange to a different policy, or 4) surrender to receive the policy cash value or sell on the life settlement secondary market for more than the policy cash value.

Weber concludes by observing that such tools and techniques provide statistical and actionable information to ILIT trustees which they can then use to manage policies in a way that is conducive to making sure beneficiaries are taken care of in ways that are consistent with the expectations of the Grantor.

Veralytic research is facts-based pulled from the industry’s largest database of pricing and performance data and useful both to institutional trustees needing in-depth suitability measurements for hundreds or thousands of policy holdings at a fraction of the cost of evaluations prepared “by hand”, and to personal trustees needing suitability information in easy‑to‑understand common financial terms. While relevant case law does not yet reference any particular research as dispute-defensible, only Veralytic research is endorsed by the New York Bankers Association (NYBA among others) for support of the duty to investigate suitability, accepted by the Financial Planning Association (FPA) for independent insurance advice, and reviewed by the chief regulatory body of the financial services industry for fair and adequate disclosure in of all types of permanent life insurance.

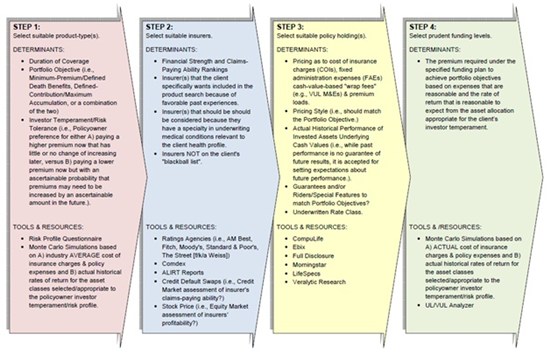

Veralytic research is but one of many tools that should be considered by ILIT trustees and advisors who work with ILIT trustees for determining and documenting life insurance product suitability. As Whitelaw cautions, overly-simplistic policy evaluations based on predatory sales/marketing practices using illustrations of hypothetical policy values are among the “red flags” that identify potential nightmares. Veralytic likewise encourages trustees and advisors alike to do your due diligence on your due diligence tools. The means, methods and judgmental techniques behind Veralytic ratings and measures are actuarially derived and fully disclosed in the User Guide (see pages 14 - 30 in this example Veralytic Research Report) and in US Patents #6456979 and #7698158. Below is a flowchart listing all the tools about which Veralytic is aware, and how they support each step in the process for the prudent selection and proper management of life insurance policy holdings.

Veralytic would like to thank again the Society of Financial Service Professionals for making this program available for Veralytic to comment on and a discount to Veralytic readers. In turn, Veralytic would like to make a special offer for FSP Members of one free Veralytic Report. Simply e-mail your illustration (with detailed accounting pages) to reports@veralytic.com along with your active FSP membership # by 6/30/2013 for your free report.

Veralytic also recommends you download the Historic Volatility Calculator (HVC) that is made available to FSP members at no cost at www.financialpro.org/HVC .

[1] Predatory practices are defined by Whitelaw as “ the conscious and willful inattention to, avoidance of and disregard for the ILIT Agreement, known ILIT trustee duties and known life insurance guidance, ignorance and lack of awareness are not defensible excuses”.